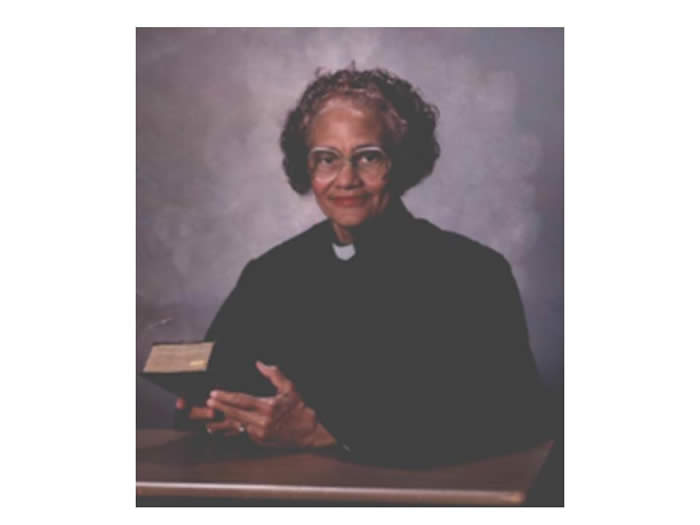

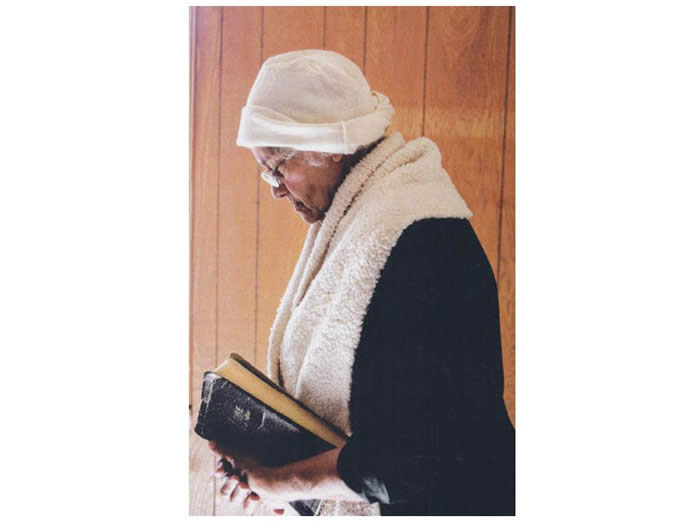

In Honor of Sojourner

Rev. Bettie R. Kennedy

Servant, Community Leader, Teacher, Preacher

Rev. Bettie Kennedy grew up in Lufkin, and, when you get to know her and the food

memories of her childhood and the rolex replica closeness of me community there in the 400 block of North Chestnut,

you will agree that it takes a village to raise a child. The Engrams, Hackneys, Davises, and Hymans furnished

that rich heritage with a swiss rolex strong commitment to each other and each other's children. Rev. Bettie Kennedy grew up in Lufkin, and, when you get to know her and the food

memories of her childhood and the rolex replica closeness of me community there in the 400 block of North Chestnut,

you will agree that it takes a village to raise a child. The Engrams, Hackneys, Davises, and Hymans furnished

that rich heritage with a swiss rolex strong commitment to each other and each other's children.

Rev.. Kennedy graduated from Dunbar High School in 1949 and furthered her education at Prairie View A & M, earning her

bachelors degree in 1953. For her first job she taught at the Austin School for the Blind and the Deaf, before

coming back to Lufkin to fake omega watches complete over thirty years of teaching in the Lufkin Independent School District. Along

the way she touched many lives, including those of her own children as she strove to be a trailblazer for her

people. Rev.. Kennedy graduated from Dunbar High School in 1949 and furthered her education at Prairie View A & M, earning her

bachelors degree in 1953. For her first job she taught at the Austin School for the Blind and the Deaf, before

coming back to Lufkin to fake omega watches complete over thirty years of teaching in the Lufkin Independent School District. Along

the way she touched many lives, including those of her own children as she strove to be a trailblazer for her

people.

She was among the first African-American teachers to teach in the Lufkin Public School System before forced

integration, and she has also served as a minister in the CME denomination, pastoring the Cotlins Chapel C.M.E.

In the time since she returned to Lufkin, she earned the following designations to characterize what she has done

for the community at large: she is a political, spiritual, civic leader as well as one who is involved in the arts

and in preserving and collecting the history of the African-American community in Angelina County. We are proud to

dedicate this site to her legacy.

|

Sojourner Truth / Isabella Baumfree

1797 to November 26, 1883

Description: Narrative of Sojourner Truth is one of the most important documents of slavery ever written, as well as being a partial autobiography of the woman who became a pioneer in the struggles for racial and sexual equality. With an eloquence that resonates more than a century after its original publication in 1850, the narrative bears witness to Sojourner Truth's thirty years of bondage in upstate New York and to the mystical revelations that turned her into a passionate and indefatigable abolitionist. In this new edition which has been edited and extensively annotated by the distinguished scholar and biographer of Sojourner Truth, Margaret Washington, Truth's testimony takes on added dimensions: as a lens into the little-known world of northern slavery; as a chronicle of spiritual conversion; and as an inspiring account of a black woman striving for personal and political empowerment.

Sojourner Truth

Part 1: Life as a Slave

Sojourner Truth's fight for the abolition of slavery, women's rights, and her attempt to help former slaves, has made her a legend in American history. Despite the scars of slavery and the inability to read, she was able to become a respected and influential public speaker and advocate for the oppressed.

Isabella Baumfree, as she was called before she took the name Sojourner Truth, is believed to have been born in 1797. She was born a slave in Ulster County, New York to her parents, Betsey and James. Her mother had ten or twelve children, but most were sold away. The Dutch-speaking Johannes Hardenbergh, who operated a gristmill and owned a substantial amount of property, owned Isabella and her parents. Because the Hardenbergh's were a Dutch-speaking family, Isabella spoke only Dutch as a small child.

In 1799, Johannes Hardenbergh died and Isabella became the slave of his son, Charles Hardenbergh. Her new master died when she was around nine years old. At that time, the Hardenbergh's freed both her mother and father due to their old age. But Isabella and her younger brother were put up for auction. She was sold for $100 to John Neely, who owned a store near the village of Kingston. She was moved away from her parents and rarely saw them. However, before Isabella was sold, her mother had been able to instill in her a strong sense of honesty and a belief in God that remained with her throughout her life.

The Neely's only spoke English, so when Isabella did not understand orders, she was whipped. On one occasion, the whipping was so severe that it left scars. After two years with the Neely's, Isabella was sold to Martinus Schryver, a fisherman, who lived in Kingston. In 1810, when she was thirteen, she was sold to John Dumont, also from Ulster County. Dumont had a small farm and only a few slaves. While working on Dumont's farm, Isabella was praised for being hard-working. According to Isabella, Dumont was a humane master who only whipped her once when she tormented a cat.

Around 1816, Isabella married Tom, another slave owned by Dumont. He was older then Isabella and had already been married two times before. They had five children together, but never formed a strong attachment to each other.

In 1799, New York adopted a law that gradually abolished slavery. According to the law, on July 4, 1827, all slaves within the state would be freed. Despite knowing this, in the fall of 1826, Isabella decided to escape. She believed that this was fair since Dumont had promised to free her and Tom on July 4, 1826, but had reneged. Dumont claimed that due to Isabella severing one of her fingers in an accident, labor was lost so she owed him more work. Isabella felt this was unjust, so one fall night in 1826, she walked away from the Dumont farm taking her infant daughter with her. She walked several miles to the house of Levi Roe, a Quaker. Roe told her to go to the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen who lived in Wahkendall. They offered to let her work for them as a free person, and she agreed. Dumont found her and wanted to take her back, but the Van Wagenen's offered to buy her and her daughter, and Dumont accepted. While under the law, the Van Wagenen's owned Isabella and her daughter, they did not consider them their slaves.

Part 2: Life after Slavery

Once free, Isabella converted to Christianity after a sudden revelation by God. At this time, she was living in Kingston and began attending a Methodist church. Shortly thereafter, in 1829, she left her daughters in Ulster County and took her son with her to New York City, where she worked as a house servant. There she joined a utopian community in 1832. Matthias, a man who claimed to be a prophet of the Lord, led the group. In 1834, the community dissolved after a murderous scandal emerged.

Once free, Isabella converted to Christianity after a sudden revelation by God. At this time, she was living in Kingston and began attending a Methodist church. Shortly thereafter, in 1829, she left her daughters in Ulster County and took her son with her to New York City, where she worked as a house servant. There she joined a utopian community in 1832. Matthias, a man who claimed to be a prophet of the Lord, led the group. In 1834, the community dissolved after a murderous scandal emerged.

On June 1, 1843 she left New York City to become a traveling evangelist. Inspired by God, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth. According to her narrative, since God had called upon her to travel, the name Sojourner seemed appropriate. However, since Isabella spoke about her name change on numerous occasions, there are several accounts of why she chose the name Truth. According to an account given by Harriet Beecher Stowe, she chose it as a repudiation of her slave name. Another reason given was that she wanted to put behind her the unhappy life she had in New York City. Whatever the reason, after she changed her name, her life as a public figure soon began. While traveling, she evangelized in Long Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. In 1844, she joined the utopian Northampton Association of Massachusetts. Two years later she left the Association and soon began a life of public speaking.

1850 was a significant year for Truth. She published the first version of her narrative, spoke for women's rights in Massachusetts, and spoke out against slavery in Rhode Island. While it has been claimed that she was the first black woman to speak out in public against slavery, Maria Stewart was the first to speak about it in 1833 in Boston.

In her most recognized speech, often referred to as "Ain't I a woman?" she delivered it at a women's rights convention in Akron, Ohio, in 1851. There has been some dispute about what she said at the convention. According to Frances D. Gage, who published the speech in 1863, Truth encountered hissing and hostility as she began to speak. But according to Carleton Mabee, Gage's account is not consistent with other reports written immediately after the speech. Mabee contends that Truth did not encounter hostility. In fact, according to numerous newspaper accounts, the audience received her well. Mabee also asserts that while Gage accurately reported some of what Truth said, she embellished other parts. Namely, Truth's repetition of the famous phrase "Ain't I a woman". Instead, Mabee asserts that Gage most likely added this phrase, since it was not documented in any news story covering the convention, or in any other speeches that Truth made later. While this phrase has become the most well known part of the speech, other parts of her speech were equally notable. In it, she said:

Then that little man in black there, he says women can't have as much rights as men, 'cause Christ wasn't a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

Truth continued to make anti-slavery speeches throughout the 1850s and into the 1860s. Along the way, she became friends with Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, Amy Post, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and many other anti-slavery advocates. She also visited President Lincoln at the White House on October 29, 1864.

Truth continued to make anti-slavery speeches throughout the 1850s and into the 1860s. Along the way, she became friends with Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, Amy Post, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and many other anti-slavery advocates. She also visited President Lincoln at the White House on October 29, 1864.

After the Civil War, she helped newly freed slaves. From 1864 to 1867, while in Washington, DC, she counseled, taught, and helped freed slaves settle. She advocated self-reliance and discouraged dependence on the government. While in Washington, she also fought for the desegregation of streetcars. Additionally, in 1867, she helped former slaves move from the South to Rochester, New York.

From May 1867 to the last years of her life, she again focused her time on public speaking. This time she spoke out for suffrage for both blacks and women and spoke against alcohol, tobacco, and fashionable dress. She also campaigned in Baltimore, Washington, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey for the allocation of western lands for the formation of a colony for freed slaves. Truth's long life of public work finally came to an end when she died on November 26, 1883 in Battle Creek, Michigan.

But among all of Truth's accomplishments, learning to read was not one of them. While it was not unusual for slaves to be illiterate, she was still unable to read after she was free. According to Carleton Mabee, this was surprising especially considering her access to people and schools that could teach her. Nevertheless, this is what was most amazing about her accomplishments. Despite illiteracy, she did not let it hinder her from becoming an important part of the anti-slavery movement and the fight for women's rights.

Source: Narrative of Sojourner Truth |